- Home

- Deepa Anappara

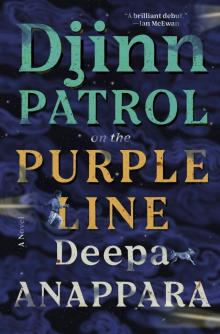

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line Page 4

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line Read online

Page 4

Quarter’s boys ended up breaking a bone in sir’s right hand. We didn’t have school for days afterward because the teachers went on strike, asking the government to protect them, but then they came back and so we had to come back too. The two boys the police finally arrested for the attack weren’t from our school, so Quarter wasn’t expelled. Kirpal-Sir stopped taking the roll call from that day onward, but he carries the register everywhere, tucked under his armpit. It’s not a secret. Even the headmaster knows sir will never expel anyone again for missing school.

Kirpal-Sir’s chalk is screeching again. Some of the boys in the front row crick their necks to look at me. I roll my upper lip and bare my front teeth. They snicker and turn away.

Pari scribbles on the newspaper that covers her Social Science textbook. Faiz has a sneezing fit. I shift to the side, so that his snot bullets won’t hit me.

“Silence,” Kirpal-Sir turns around and shouts. I think he says silence more often than any other word; he must yell it in his sleep. He lobs the chalk-stub in my direction. It misses me and falls between my desk and Pari’s.

“But, sir,” I say, “I didn’t do anything.”

He picks up the register with his left hand and flick-flicks the pages with his floppy right hand.

“Here you are,” he says. He raises his eyebrows at me when he says you. Then he removes the pen clipped to his shirt pocket, writes something on the page, slams the register shut and drops it on the table. “There, it’s done. Happy?”

I don’t know why I should be happy.

“What are you still doing here?” Kirpal-Sir says. “Jai, come on, pack up your things. I have marked you absent for the day, just as you wanted. Huzoor, this means you’re getting a day off”—now he sweeps both his hands toward the classroom door—“out you go.”

“If just like that you’re getting a chutti,” Faiz says, “take it, yaar.”

I don’t want a day off. I don’t want to miss the midday meal because then I’ll have to go hungry until dinner, which is more hours away than I can count on my fingers.

“Out, now,” Kirpal-Sir says. The whole class is silent. Everyone is shocked that sir is showing his anger instead of swallowing it whole like he usually does.

“Sir—”

“There are other students here who, unlike you, want to learn. They hope to become doctors and engineers and suchlike. But”—spit bubbles at the corners of his mouth—“your calling is to be a goonda. It’s best you learn about that outside the school gate.”

The anger in my stomach hops to my chest and my arms and legs. I wish Quarter’s boys had killed Kirpal-Sir. He’s a terrible teacher.

I push my things into my bag, go out into the corridor, and stand on the tips of my toes to peer outside the school wall. Maybe Quarter is there. I’ll ask him if I can become a member of his gang.

Kirpal-Sir barges into the corridor, his face dotted with strange winter-sweat, and says, “Oye, loafer, didn’t I tell you to leave? No free lunch for you today.”

I have been sent out of the class before, because I forgot to do the homework or got into a scrap, but I have never been thrown out of the school. I walk toward the gate, stopping to kick the penguins, and don’t look back even once. I’m going to leave school for good and take up a life of crime, just like Quarter. I’ll be the scariest don in all of India and everyone will be frightened of me. My face will come on TV but I’ll hide behind large, dark glasses and I’ll look a bit like me but no one will be able to tell for sure, not even Ma or Papa or Runu-Didi.

I WALK AROUND BHOOT BAZAAR, IMAGINING MY LIFE—

—as a criminal. It won’t be easy. I’ll have to grow taller and heavier because only then will people take me seriously. Right now, even shopkeepers treat me like a scruffy dog. When I squash my nose against the glass cabinets in which they display their wares—orange rows of Karachi halwa and half-moons of gujiyas decorated with powdered green cardamom—they poke me on the head with broomsticks and threaten to douse me with mugs of cold water.

My feet slip through the holes in the pavement. “Beta, watch your step,” says a chacha whose face is as wrinkled as my shirt. He’s sipping chai in a tea shop that juts out into the lane. Playing on a radio at the shop is an old Hindi film song that’s Papa’s favorite. “This Journey, So Beautiful,” the hero sings.

The men sitting next to the helpful chacha, on knee-high barrels and upturned plastic crates, don’t see me. Their eyes are full of sadness at not being picked for a job today. All morning they must have waited at the junction near the highway for the contractors who arrive in jeeps and trucks to hire people for laying bricks or painting walls. There are too many men and too few contractors, so not everyone gets work.

Papa used to wait at the highway too until he got the good job at the Purple Line metro station and then the building site. He has told me about beastly contractors who steal money from workers and make men swing from tattered rope harnesses to clean hi-fi windows. Papa says he doesn’t want that dangerous life for me, so I should study well and get an office job and be hi-fi myself.

My eyes sting when I think of how ashamed he’ll be if I become a criminal. I decide I don’t want to be Quarter 2 after all.

* * *

I turn into the alley that leads to our basti and cough with my hand covering my mouth. This way, if a lady from Ma’s basti-ladies’ network sees me and snitches to Ma about me cutting classes, she’ll also have to say that I looked quite sick.

I realize that my cough is as loud as an airplane. Something is not right but I can’t tell what. I stop and look around. Hold my breath and listen. My heart knocks against my ribs. I open my mouth wide and blow my breath out and catch it back like Baba Devanand does on TV. Slowly the knots in my stomach loosen. Then I see what’s wrong.

The alley is quiet and empty. Everyone is missing, the grandpas reading newspapers, the jobless men playing rummy or bluff, the mothers soaking clothes in old paint tubs, and the little children waddling around with mud-caked knees. Dirty vessels, some of them half-washed, are scattered around the plastic water barrels that guard every door in the basti. Something rumbles behind the smog. Maybe it’s a djinn. A bad feeling flickers through me. I want to pee.

A door to my left creaks open. I jump. I’m going to be snatched. But it’s just a woman in a sari. She has vermillion paste in the parting of her hair, and it’s smudged all over her face.

“Boy, don’t you have a brain on you?” she bellows. “There are policemen everywhere in our basti. You want them to catch you?”

I shake my head, but I stop feeling like I have to go to the toilet. Policemen are scary but not as scary as djinns. I want to ask the woman why the cops are here and if they have brought bulldozers with them to frighten us and shouldn’t someone start a bucket collection to pay them off, but instead I say, “You have got sindoor on your cheeks.”

“What will your mother think?” the woman asks. “She’s working so hard that she doesn’t have any time to pray at the temple, and just look at you. Cutting classes and enjoying yourself, haan? Don’t do this, boy. Don’t disappoint your mother. Go back to school now. Otherwise you’ll regret it one day. You understand what I’m saying?”

“Understood,” I say. I don’t think she and Ma are friends.

“Don’t let me catch you again,” she says and shuts the door in my face.

I can’t believe Bahadur’s ma got the police to come to our basti. That’s why everyone’s hiding. I should hide too, but I also want to find out what the policemen are doing. They are supposed to Serve and Protect us, but the cops I see around Bhoot Bazaar only ever do the opposite of that. They pester shopkeepers, fill their tummies with free food from the carts of vendors, and ask anyone late with a hafta payment to choose between a baton up their backside or a visit from the bulldozer.

The smog proves useful for once because it

gives me good cover. I stick to the sides of the lane, close to the water barrels, even though the ground is squishy there because of all the vessel-washing. I pass two pushcart vendors covering their vegetables and fruits with tarpaulin sheets. Three cobblers squat nearby, the black bristles of their shoeshine brushes poking out of the sacks slung over their shoulders. They are on their marks to get set, go at the first whiff of trouble.

I’m not scared like these men. I’m not spineless either, like Shanti-Chachi’s second husband. Everyone says he does whatever chachi asks him to do: cooks for her, washes her underskirts, and hangs them out to dry even when the whole lane is watching him. As a midwife, chachi makes loads more money than her husband too, even though he has two jobs.

I see Buffalo-Baba in his usual spot in the middle of a lane, and a policeman in a khaki uniform. Watching the cop are Fatima-ben, worried perhaps that the policeman will do something bad to her buffalo, grandpas with their hands folded across their chests, mothers with babies on their hips, children who don’t go to school so that they can do embroidery or snack-making work at home, and Bahadur’s ma and Drunkard Laloo even though they don’t live on this lane.

I edge closer, ducking under clotheslines heavy with wet shirts and saris, their hems brushing against my hair. Just two houses away from where everyone is standing is a black water barrel by a closed door. It’s the perfect hiding place. I put my school bag down, crouch behind the barrel, and make my breathing shallow so that no one can hear me. Then I peek out with one eye.

The policeman prods Buffalo-Baba with his shoes and asks Drunkard Laloo, “So it’s true? This animal never gets up? How does it eat?”

Maybe this policeman thinks Buffalo-Baba is hiding Bahadur under his dungy backside.

A second policeman steps out of a house. He’s wearing a khaki shirt that has red arm-badges shaped like arrowheads pointing down.

Only senior constables wear such badges. I know because last month I saw a Live Crime episode about a crook who fooled people by putting on a senior constable’s uniform. The fake cop even went to the police barracks in Jaipur to drink tea with the real cops there and left with their wallets.

“Making friendship with a buffalo? Good, good,” the senior constable says to the policeman whose khaki uniform doesn’t have any badges stitched to the sleeves, which means he’s only a junior. Then the senior steps over Buffalo-Baba’s tail to stand in front of Bahadur’s ma.

“Your boy, he has a problem, is what I have come to understand,” the senior says. “He’s slow-brained, isn’t he?”

“My son is a good student,” Bahadur’s ma says. Her voice is raspy from crying and shouting but it’s got a red glow to it because it’s smoldering with anger. “You ask at his school, they’ll tell you. He has a little problem speaking, but the teachers say he’s getting better.”

The senior constable purses his lips and breathes air into Bahadur’s ma’s face. She doesn’t even wince.

“In my opinion,” the junior constable says, “the best thing to do is wait for a few days. I have seen many such cases. These children run away because they want to be free, then they come running right back because they realize freedom doesn’t fill their stomachs.”

“Although,” the senior says, “it appears your husband…now…how can I put it”—he glances at Drunkard Laloo, who hangs his head—“was violent with your son?”

A scratchy silence fills the lane, broken by the clucks of hens that have escaped from clumsily bolted wire cages and the bleats of a goat from inside a house.

No one in our basti wants Drunkard Laloo to end up in prison. But we shouldn’t lie because the senior constable is smart. I can tell because he’s young like a college student and already a senior, and he’s asking questions exactly like the good-cop types on TV. He doesn’t want our money. His only mission is to put bad guys behind bars.

“Saab, once or twice who doesn’t beat their children, haan, saab?” a man standing near Drunkard Laloo answers for him. “That doesn’t mean they should run away. Our children are more intelligent than we are. They know we want the best for them.”

The senior constable studies the man’s face and the man laughs nervously and looks elsewhere, at the silvery insides of empty namkeen packets on the ground and the small children trying to shake off their mothers’ hands holding them back.

Drunkard Laloo opens his mouth. No words come out. Then he shivers as if a current from the earth is shooting up through his legs and hands.

Pari and Faiz won’t believe me when I tell them what I’m seeing now. The best thing is that my grey uniform is good camouflage in the smog.

“You,” the senior constable shouts, pointing at me. “Come here right now.”

My head slams against the barrel as I hunch down quickly but I know I haven’t been quick enough. He’ll shove your shit up your mouth, I think. It’s something I once heard my Muslim-hater classmate Gaurav say; he was talking about what Quarter would do to anyone who crossed him.

“Where’s he gone? Where’s the boy?”

My eyes lock on the white plate of a dish antenna angled toward the sky, attached to the edge of a tin roof across the lane. If I look at it with both my eyes, really look at it, I won’t be able to see anything else. Everyone will disappear, even the policeman.

But he’s standing at my side with his fingers drumming the lid of the water barrel. He takes off his khaki cap. Its tight elastic band has left a blotchy red line in the middle of his forehead.

“Let’s see if this fits you better,” he says, smiling and waving the cap in my face.

I shrink back from the cap that smells like armpits, and jails maybe.

“Don’t want?” he asks.

“No,” I say, and my voice is so weak even I can’t hear it.

The policeman places the cap back on his head but doesn’t pull it down. Then he scrapes the mud off his black leather shoes against a brick. The sole of his left shoe falls slack-mouth open, and loose stitches tremble like threads of spit. His shoes are torn exactly like my old ones.

“No school today?” he asks.

I haven’t been coughing, so I say, “Dysentery. The teacher sent me home.”

“O-ho,” the policeman says. “You ate something you shouldn’t have, didn’t you? Mummy’s cooking not to your liking?”

“No, good, it’s very good.”

Everything is going wrong today and it’s all because of Bahadur.

“This boy we’re looking for,” he says, “you know him? He’s in your school?”

“Same class only.”

“Did he say anything about running off?”

“Bahadur can’t speak. Stutter he has, right? He can’t make words like proper children.”

“What about his father?” The senior constable lowers his voice. “The boy said anything about his father beating him up?”

“Could be, that’s why Bahadur ran away. But Faiz thinks djinns took him.”

“Djinns?”

“Faiz says Allah made djinns. There are good and bad djinns same as there are good and bad people. A bad djinn might have snatched Bahadur.”

“Faiz is your friend?”

“Yes.”

I feel a bit guilty about snitching to the senior constable but I’m helping him in his investigation. Something I say will turn out to be a big clue that will help him crack the case. Then a child actor will play me on a Police Patrol show. It will be called The Mysterious Disappearance of an Innocent Slum Boy—Part 1 or In Search of a Missing Stutterer: A Heartbreaking Saga of Life in a Slum. Police Patrol episodes have brilliant names.

“We don’t have enough space to hold people in our jails. Now if we start arresting djinns too, where will we put them?” the policeman asks.

He is making fun of me, but I don’t mind. I just wish I knew what he’s waiting f

or me to say so that I can say it and he can find Bahadur. Also, my neck is hurting from looking up at him.

The policeman scratches his cheeks. My stomach growls. Faiz usually helps me shush it by giving me the sugar-coated saunf he carries in his pockets, stolen from the dhaba where he works on some Sundays as a waiter.

“Maybe Bahadur was bored here, you think?” the policeman asks.

My stomach rumbles again and I push it down with my hands so that it will stay quiet. “Did his ma say that?” I ask. “She called you, didn’t she? We never go to the police.”

I have said too much but the policeman’s face is empty. He hitches his khaki trousers up, straightens his cap, and turns to leave.

“There’s a cobbler two lanes away,” I say after him.

He stops and looks at me as if he’s only seeing me for the first time now.

“For your shoes,” I say. “He’s very good. His name is Sulaiman and after he stitches the shoes, they’ll look like there are no stitches only and he—”

“Has the president awarded him a Padma Shri too for his service?” the policeman asks. I don’t answer because it’s a joke but not a funny one.

He struts back to where everyone is standing. He nods his head at the junior constable, three sharp nods that are part of a secret signal like the ones between bowlers and fielders on a cricket field. Pari, Faiz, and I should make up a secret signal too.

“Nothing to see here,” the junior constable shouts. “All of you, and I mean all of you, go back to your homes.”

The fathers and mothers and children run inside, but a brown goat, dressed in a spotted sweater that makes it look like it’s part leopard, comes out of a house and butts its head against the junior constable’s legs.

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line

Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line